Flock's drone insurance allowed operators to pay small sums to offset risks on individual flights, but the company has now left the marketplace.

OXFORD, England—Even if, as an innovative startup active in the advanced air mobility (AAM) sector, your company has solved all the challenges around power, propulsion, aerodynamics, logistics and production, there is still one other element which could make or break your project.

Insurance is vital for any business to obtain, but convincing an insurer to take a risk on an unprecedented product or service may be trickier than inventing a new technology.

“Insurance underwriters are looking for a risk reward,” says Matthew Day, a director in the UK division of insurance firm Gallagher. He spoke at London Oxford Airport’s inaugural Disruptor’s Day held here at the airport in September. “Is it worth doing for them? They’re only doing [insurance] because they can make money. They’re not doing it for any altruistic reasons. So, is it a product or an industry that they want to be insuring?”

Day argues that aviation has a structural challenge that makes it potentially less appealing to insurance underwriters than other transportation sectors, regardless of the level of maturity of the specific product or service. That is volume.

“[Insurers] are looking at putting money at risk into an activity where there is scale: in simple terms, that the premiums of the many pay for the losses of the few,” Day says. “If you’re asked to insure a million cars, you’d be a lot more confident than insuring one eVTOL [electric-vertical-takeoff-and-landing] passenger jet.”

A further complicating factor for AAM developers is that underwriters typically also look for data sets that help quantify risk. When a technology is new, there may be insufficient data to evaluate risk with any confidence. Perhaps for new platforms developed by established companies, some read-across from previous programs will help inform the calculation. But in a field like AAM, dominated by startups with no previous programs to generate confidence-building data sets, the challenge is magnified.

Perhaps the nearest to a like-for-like example that the AAM sector may be able to use to develop underlying data-based confidence is the commercial drone industry, Day says. Yet there will be significant barriers to a straight read-across of detail, not just because of the considerable differences in the technologies and their use cases, but because thus far there has yet to be a drone-related incident that generated a significant insurable loss.

“Aviation—and emerging technologies of any type—lacks awareness of an outcome,” Day says. “We all understand that a drone, at some stage, may actually cause a significant aviation accident—at which time we’ll suddenly know what the [financial] exposure is. It’s rather difficult to price the product until you have the evidence—and it’s very difficult when there is a new, emerging technology, because there is no evidence.”

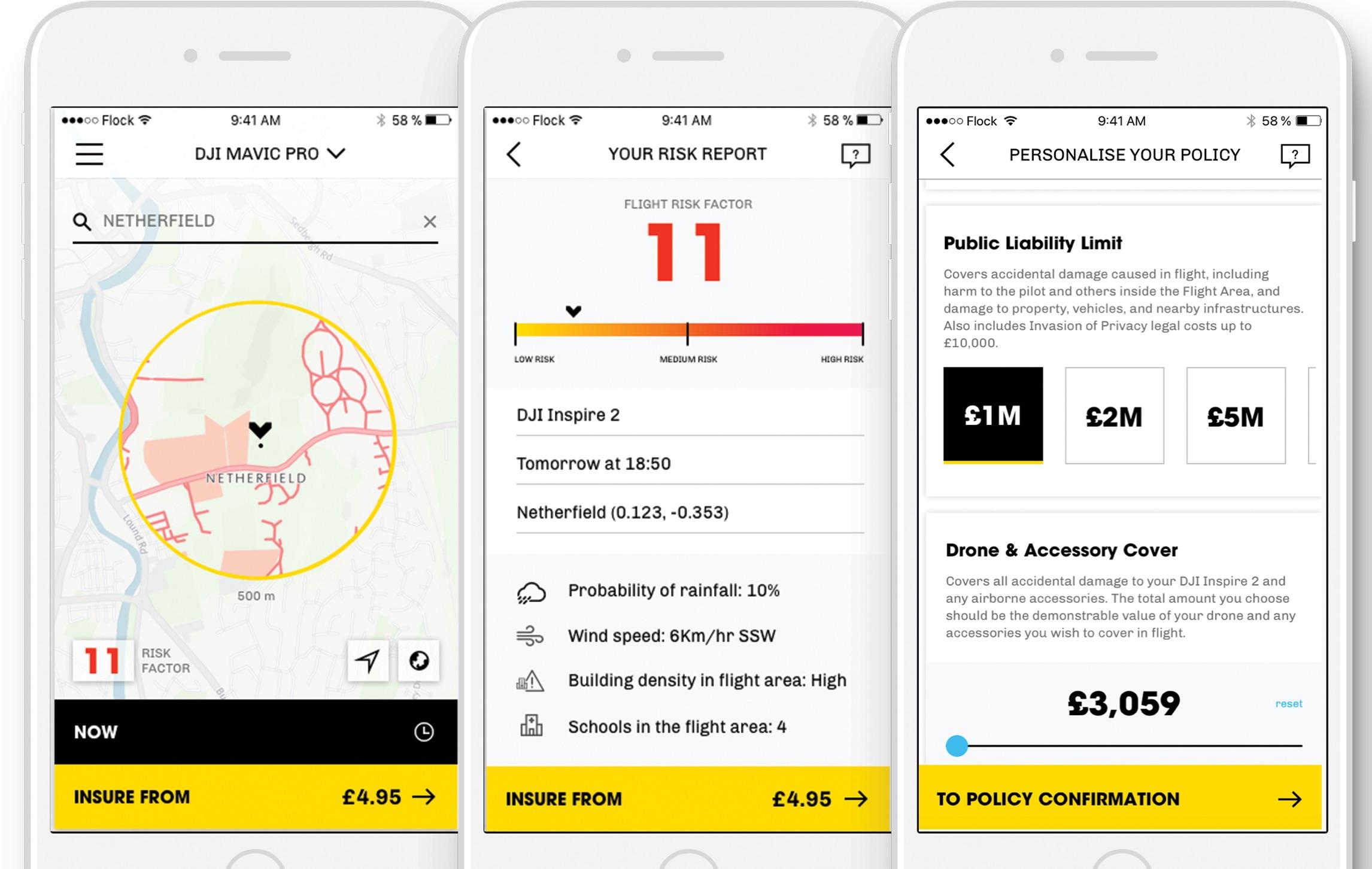

Attempts have been made to square this circle in the drone industry. A London-based startup, Flock, was established in the mid-2010s to address the growing market of commercial drone operators who found traditional annual policies to be prohibitively expensive. They developed an app-based pay-per-flight product that more accurately reflected the risk of the specific operation rather than relying on a blanket approach to covering every conceivable flight profile—most of which the customer was unlikely to ever undertake. But Flock exited the drone-insurance business in 2022.

“Flock realized there are insufficient units of commercial drones in the UK to justify a business model,” Day says. “They have pivoted themselves and now they do trucking, haulage insurance—because if there are a thousand commercial drones in this country, there are a million trucks. They’ve moved from one class of business to another where the scale is enough to make it viable. If you’ve only got 100 units and five of them fail, the cost of them wipes out the premium base in a heartbeat.”

The key to unlocking this seemingly intractable problem, Gallagher suggests, is open and honest dialog between developers and insurers. The cost of not engaging early with insurers could be the loss not just of an aircraft or a single business, but of the entire sector’s financial underpinning.

“Yes, you’ve got to communicate with the regulators. Yes, you’ve got to communicate with your would-be buyers. But you will need to communicate with your risk takers so that they understand what you’re trying to achieve,” he says. “The better they understand it, the more willing they are to support it, the more able they are to enable you to grow and support the business.

“If we in the insurance industry don’t know what’s going on, then we will always presume the worst, and [that] will impact adversely on the business—in simple terms, [by] not providing insurance,” he adds. “If there’s no insurance, then the billions of pounds invested in the industry would quickly go and find an industry where there is insurance.”