Rosetta Points to OSIRIS-REx, Hayabusa 2 to Solve Earth's Water Mystery

The Earth's abundant supply of water appears to have been delivered by asteroids as they pelted the early Earth rather than icy comets, according to somewhat surprising results from the early science phase of the European Space Agency's long running Rosetta mission to the comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko.

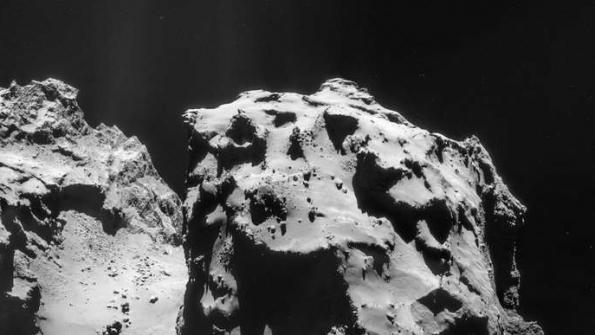

Rosetta, launched a decade ago, rendezvoused with the comet on Aug. 6 and will escort the oddly shaped 4 kilometer dirty ice ball around the sun and out towards Jupiter in the coming months to observe the solar interactions.

In the weeks following the initial encounter, one of Rosetta's 11 science instruments, the Rosina mass spectrometer, began to measure the deuterium-to-hydrogen ratio (D/H) in the water vapor from the comet to determine whether it matched that of the Earth's water. It doesn't, and the comet's D/H ration is more than three times that found in the terrestrial oceans. Deuterium is a normal hydrogen atom nucleus plus a neutron.

The findings, published in Dec. 10 editions of the journal Science represents the work of 32 researchers from a half dozen countries, including the U.S.

"We knew that Rosetta's in situ analysis of this comet was always going to throw up surprises for the bigger picture of solar system science, and this outstanding observation certainly adds fuel to the debate about the origin of Earth's water," said Matt Taylor, ESA's Rosetta project scientist.

Prevailing theories held that the high temperatures accompanying the formation of the sun and planets 4.6 billion years ago would have boiled away any water native to the Earth. Yet 7/10ths of the Earth's present day surface is covered with water, suggesting the liquid came from an external source after the planet cooled, perhaps a lengthy pelting by comets and asteroids 800 million years after the solar system formed, known as the Late Heavy Bombardment.

But which one, comets or asteroids? The D/H ratio, which varies with distance from the sun and time, offers a way to differentiate.

Comets, comprised of materials that formed the planets, claim two heritages. Some formed in the Uranus/Neptune space and migrated to a distant region called the Oort Cloud through gravitational interactions with the gas giant planets. 67P/ChuryumovGerasimenko belongs to another family of comets that formed beyond Neptune as icy settlers of the Kuiper Belt.

Rosetta's comet swings around the sun every 6 1/2 years on a path that comes as near as the region between the Earth and Mars and beyond Jupiter at its most distant.

In all, the D/H ratios of 11 Oort Cloud and Kuiper Belt comets have been measured. Of those, only one, the Kuiper belt comet 103P/Hartley-2, reflected a D/H ratio similar to water on Earth in observations made by ESA's Herschel probe in 2011.

The Hartley-2 measurements bolstered the Kuiper belt comets as a potential terrestrial water source -- until Rosetta's comet encounter.

"So, that's a new result and we have to conclude the following," said Kathrin Altwegg, the Rosina spectrometer’s principal investigator from the University of Bern in Switzerland and lead author of the Science journal report. "First the terrestrial water was probably brought by asteroids more likely than comets. And secondly, that Kuiper Belt comets were probably not all assembled in the same location in the solar system. We have a mixture of comets in what we call today the Kuiper Belt."

The case for asteroids as a more probable water source is strengthened by the D/H ratios of meteorites, fragments of asteroids that fall to Earth. They exhibit terrestrial D/H ratios, suggesting that many asteroids, which have a lower water content, would have struck the Earth to deliver the quantity of water evident today.

NASA's OSIRIS-Rex asteroid mission, set to launch in September 2016, may help to answer the question. The spacecraft is to reach the asteroid Bennu, which has a high probability of striking the Earth late in the 22nd century, in October 2018. The 400 day encounter is to include the collection of a small piece of Bennu, a typical carbon rich asteroid, for return to Earth in 2023 and subsequent analysis.

Meanwhile, Japan's Hyabusa2 spacecraft launched on a similar mission Dec. 3 to another carbon rich asteroid, 1999 Ju3. It, too, is to reach its destination in 2018 for a prolonged visit and sample collection. Hayabusa2 should return to Earth in 2022.