As NASA’s Artemis program strives to establish a sustainable human presence at the Moon, the astronauts will be exploring the lunar south pole—a landscape that promises to yield discoveries about how the Solar System formed, including the violent processes that preceded life on the Earth.

Much of the lunar south pole’s exploration appeal is the prospect for large water ice deposits in permanently shadowed regions of cratered terrain. Once extracted, water ice could provide a resource for water and oxygen life support, liquid hydrogen and oxygen for rocket propellants as well as a liquid source for radiation shielding as humans advance to live and work on the Moon.

But samples of the regolith, or surface soil, boulders and rocks that Artemis astronauts will be equipped to gather and return to Earth hold a scientific bounty as well.

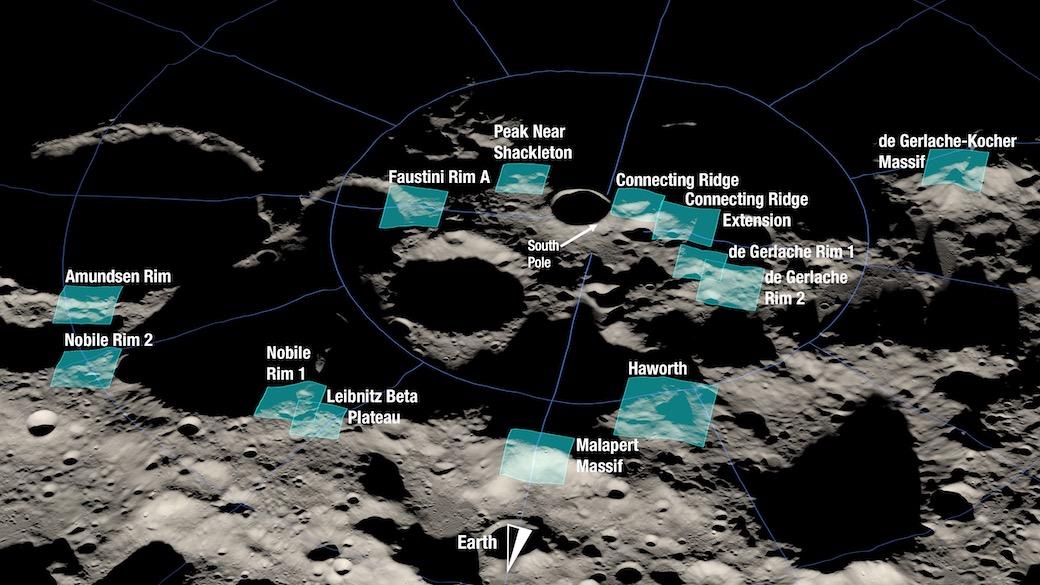

NASA is assessing 13 candidate landing sites for the Artemis III mission, which is scheduled to return two yet-to-be-selected astronauts to the lunar south pole for about 6.5 days that will include at least two extravehicular activities, each at least 4 hr. long. More astronauts and longer surface stays are planned as more Artemis missions follow and establish a lunar base camp.

Though targeted for launch in December 2025, Artemis III will likely move into 2026 or later in response to recent debt-limit legislation and technical challenges associated with the development of SpaceX’s Human Landing System. It is planned to transport Artemis astronauts between lunar orbit and the surface of the Moon.

Each of the candidate landing sites will feature influences from the Moon’s South Pole-Aitken basin, a 1,550-mi.-wide (2,500-km), 5-mi.-deep impact basin on the Moon’s far side that formed an estimated 3.9 billion to 4.6 billion years ago and is one of the largest impact features in the Solar System.

These impact influences include mountains and surface regolith that was once ejecta from the impactor and is now spread across the Artemis candidate landing sites at depths of thousands of feet, explained David Kring, principal scientist at the Lunar Planetary Science Institute in Houston, during a June 8 presentation.

NASA’s Apollo program conducted six human lunar landings from July 1969 to December 1972, each with two astronauts and lasting only a few days, and all in the equatorial region of the Moon. The regions they explored and sampled are estimated at about 3.6 -3.7 billion years in age, or perhaps slightly older at the Apollo 14 and 16 landing sites.

“This is the age of Artemis exploration. The zone is bigger by a lot. So we will get a glimpse at a completely different epoch of lunar history, which is interesting for a lot of reasons,” Kring said of the lunar south pole region.

“The zone represents and by and large is going to provide astronauts samples of rocks that are older than any rock on the planet Earth. These rocks pre-date the earliest isotopic evidence of life on Earth, and in fact will give us a better assessment of those early Earth conditions because basically what happened on the Moon was happening on the Earth,” Kring added.

While the Earth and Moon are separated by about 21 Earth radii, that distance was only about 4 radii in that early epoch of the Solar System.

“Artemis astronauts will be picking up rocks older than the Earth’s continents, and if they are lucky, they will discover the oldest vestiges of our own planet Earth on the Moon,” Kring said.