In the years since the COVID-19 pandemic emerged, bankers and advisors in mergers and acquisitions (M&A) have been looking for signs of a long-awaited consolidation in the aerospace and defense supplier base.

One group now thinks the engine manufacturing subsector will rev up as the next dealmaking hotspot.

On or around Thanksgiving Day in the U.S. (Nov. 24), a group of private-equity (PE) investors signed a deal to swap ownership of two Connecticut-based engine-machining companies, Paradigm Precision and Whitcraft Group, which in turn are being merged. The complicated deal includes one PE firm, Greenbriar Equity, selling Whitcraft out of one of its investment funds and then buying back into the merged entity via a new fund.

Other actions included global investment giant Carlyle selling Paradigm to Clayton, Dubilier and Rice (CDR), who counts Ray Conner as operating advisor. He was the former president and CEO of Boeing Commercial Airplanes and will become chairman of the combined company upon consummation of the transactions, expected in “early” 2023. Financial details otherwise were not provided.

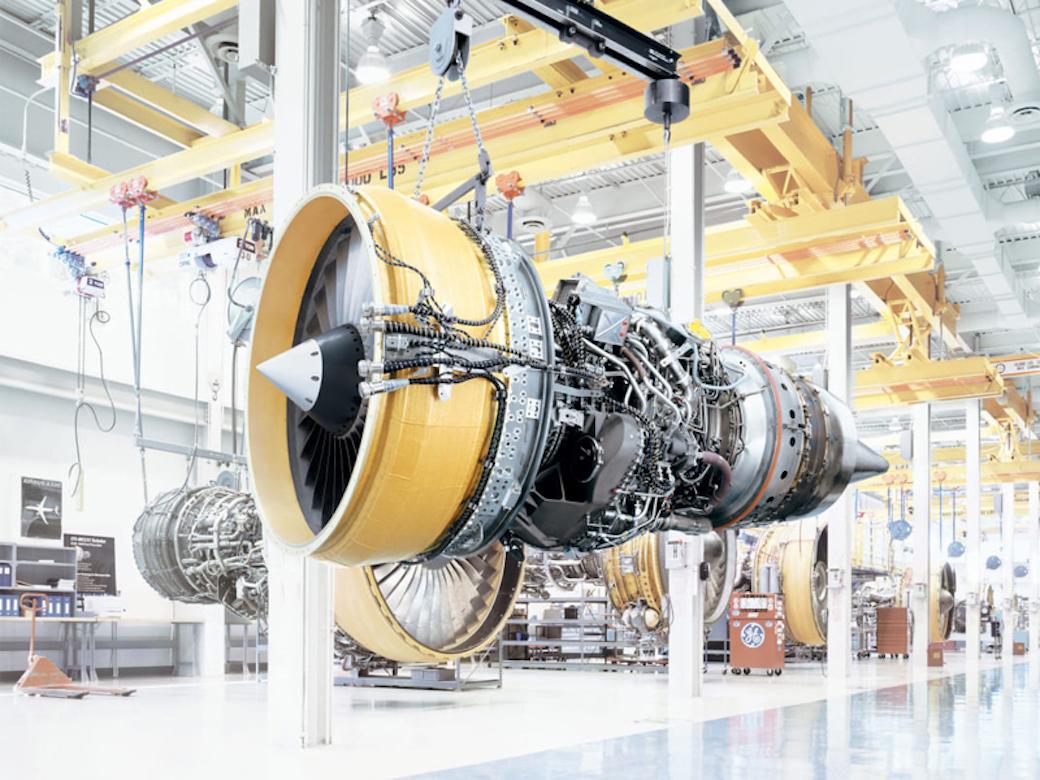

While the financial maneuvers are interesting—admittedly more to bankers and consultants—they nonetheless underpin the strategic belief that engine-machining could be ripe for profit-taking this decade. That thesis begins with the widely expected ramp-up in commercial and business aviation production, as forecast by OEMs Airbus, Boeing, Embraer and others.

But because of the pandemic-induced two-year falloff in manufacturing, there is so much slack in the supplier base and many of those companies already were financially extended before the coronavirus hit. Thus, many could be in a position to sell.

Take Whitcraft, which Greenbriar bought in 2017 and then instigated a late-cycle roll-up effort that engulfed at least five other companies on the eve of COVID-19 and the worst of the Boeing 737 MAX debacle. In September 2020, Whitcraft started auctioning several plants across the U.S. under a retrenchment effort. The machinery came from factories that were acquired in the acquisition spree—in Fort Lauderdale, Florida; Scarborough, Maine; and Tempe, Arizona. Meanwhile, Carlyle had looked to sell Paradigm in 2019.

Integrated together, Paradigm and Whitcraft will save money by consolidating back-office and other functions while being able to set their prices better as a larger, more unified company. Before the deal, Paradigm supplied to Pratt & Whitney military engines and General Electric programs, among others. Whitcraft provided to Pratt commercial programs. They further will benefit from a low-cost country footprint for manufacturing in Mexico and Tunisia.

“We look forward to bringing together the best of both of these companies by driving operational improvements and an increased capability set that we believe will benefit customers and the commercial and military aviation engine market at large,” Conner says in the announcement.

The deal comes after a relative hibernation in the subsector. According to a September presentation by Stephen Perry, managing director at aerospace and defense investment bank Janes Capital Partners, there were only seven engine and related deals in the previous 13 quarters. That was far below the 18 aerostructures deals or 145 in machined and cast parts. Deal prices—scored in multiples of the total enterprise value of a company divided by the expected pretax earnings—were around 12.1x for engines, in the middle of two dozen industry segments he tracked.

The cast of bankers, advisors and lawyers that shepherded the deal to closure is vast and included Michael Richter, a Lazard managing director and global head of the firm’s aerospace and defense investment banking group. He told Aviation Week there could be 7-8 other engine manufacturing suppliers whose sales could be pushed along by the Paradigm-Whitcraft announcement Nov. 30. While that deal involved only PE investors, Richter knows of “strategics,” i.e., aerospace businesses that might be interested in related consolidation plays.

Why now? There are multiple reasons. For starters, the industry seems to be over the worst of the pandemic and MAX crises and is in a steadying recovery phase, albeit slow and far from the pre-pandemic business activity peaks. In turn, production-rate forecasts have been reset and are more believable going into 2023. Meanwhile, the financial costs of doing deals—while rising—are still coming off historic lows. And, unfortunately, several suppliers increasingly are being strained as they face the need to invest in new staff and production technology ahead of the ramp-up, while the pandemic-era stimulus wears off.

“The values are much better today, earlier in the cycle, than when they start operating at full-rate production,” Richter said. “Instead of blowing the doors out.”