Around a decade after preparing to divest its aerostructures businesses, Airbus is now reversing course and wants to keep component manufacturing inside the group for the long term.

Aerostructures are “a core activity of Airbus,” CEO Guillaume Faury told reporters at the company’s virtual annual press conference Feb. 18.

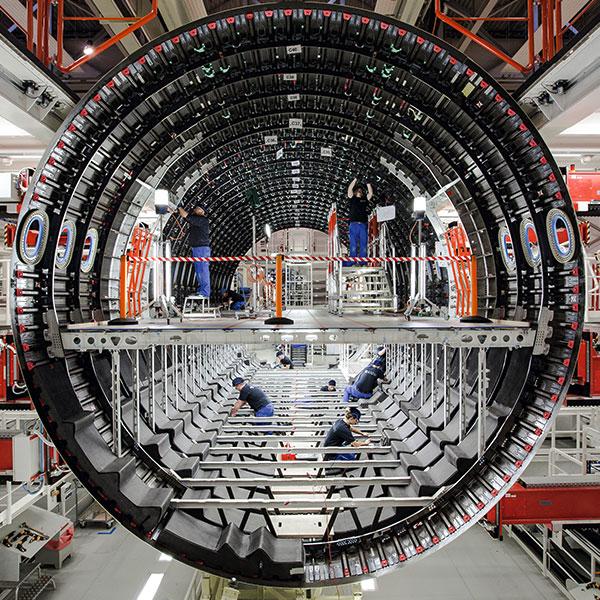

Airbus carved out several of its German and French sites at the beginning of 2009 with a view of divesting them at some point to focus the group on design, system integration and aircraft final assembly. However, the units were never sold. German subsidiary Premium Aerotec includes sites in Augsburg, Nordenham and Varel. At the same time, what was then called Aerolia was set up in France, comprising factories in Méaulte and Saint Nazaire; Aerolia merged with Sogerma to form Stelia Aerospace in 2015.

“The connection between design and production will be far more important,” Faury said. He was referring both to the ongoing move to Airbus’ digital design manufacturing and services (DDMS) program as well as changing requirements forecast with future aircraft models. Faury predicted that aircraft architecture will change significantly and aerostructures therefore will be “an important part” of that process, which “has to remain in Airbus.”

Boeing divested its Wichita, Kansas-based aerostructures business to form Spirit Aerosystems in 2005.

The decision to keep Premium Aerotec and Stelia inside the group permanently will be an important aspect in Airbus’ efforts to simplify its European industrial base, which Faury highlighted as a priority for the coming years. He left open whether and to what extent reintegration of the two subsidiaries will be pursued. Putting their activities in separate units had helped reduce complexity at the Airbus Group level, but it has led to double structures at the unit levels as the two were aiming at building up their own core functions ahead of possible sales to new investors.

Airbus’ industrial streamlining is planned to go beyond Premium Aerotec and Stelia, however, and includes the manufacturer’s primary sites across Europe. “There is a lot of potential for simplification at the European bases,” Faury said. The process is not expected to lead to the closing of any sites or to further outsourcing to bases outside of Europe such as in China or the U.S.

Faury also made clear that UK plants in Broughton and Filton will remain key to Airbus wing production in the future in spite of the fact that the country is no longer part of the European Union following Brexit.

The efforts for a more efficient internal industrial system that is not based on major divestitures is part of a broader exercise of Airbus to adjust to post-pandemic demand and production rates—a process that Faury described as very challenging, even as far as planning assumptions are concerned.

“I don’t know what being prudent actually means right now,” he said referring to production planning. “The short term is getting worse, the mid- and long term looks better,” he said. “That is a contradiction that is very difficult to manage.”

Nonetheless, Airbus is sticking to its earlier plans to begin a relatively slow ramp-up of single-aisle production, going from 40 aircraft per month to 43 in the third quarter and to 45 in the fourth quarter. “We expect a very backloaded 2021,” he said.

The slow increase in production is also seen as a preparation exercise for a much steeper ramp-up that Airbus still believes is likely in 2022. Faury expects demand to be “much stronger than in 2021” but still short of justifying former peak production rates of 60-plus narrowbodies per month. The Airbus CEO pointed out, however, that the company can boost output very fast because the tooling and infrastructure for much higher rates is already in place with staff levels being the key potential bottleneck for a fast expansion of production.

Airbus still expects a full recovery of air travel demand to pre-crisis levels between 2023 and 2025. Faury was also clear in predicting that the market will “be similar to what it was before the crisis,” though the environmental agenda will be much more important. “Businesses need to fly again; they are eager to restart projects.” Also, “people are impatient to fly again” for holidays and on other private trips.

Demand for widebodies will be lower for longer, Faury conceded. He hinted that Airbus may reduce A330neo production “slightly” below the current two aircraft per month rate, though for now it is not making that decision. The A330neo will be part of the Airbus portfolio “for the long term.” The planned new final assembly line for the A321neo in Toulouse is “on ice” for now but is “likely to be restarted.”

Airbus 2020 revenues dropped 29% to €49.9 billion ($60.2 billion). The company made a €510 million operating loss and a €1.1 billion net loss for the full year. Free cash flow was negative €7.3 billion.

Airbus adjusted the value of its order backlog downwards by €98 billion (to €373 billion). Several factors influenced the move, including the devaluation of the U.S. dollar. Around 10% of the reduction was due to aircraft deferrals and cancellations caused by the COVID-19 pandemic.

In the fourth quarter Airbus generated €4.9 billion in cash as it managed to deliver aircraft way above average production rates for the year.

In 2021, the company plans to deliver at least as many commercial aircraft as in 2020 (566). Its adjusted earnings before interest and taxes (EBIT) is expected to reach €2 billion, €300 million higher than this year. And cash-flow before mergers and acquisitions and customer financing will be at least at break-even, according to the outlook. However, CFO Dominik Asam said Airbus may have to finance deliveries of €1 billion or more in 2021, though it is betting on strong support from export credit agencies.

Comments

"You have to smell your business"